why GLIAl cells?

WHAT ARE GLIA?

Glia are a collection of non-neuronal cells that are important for the development and healthy function of central nervous system (CNS) tissue in the brain and spinal cord. Glia together with neurons comprise the parenchymal unit (functional tissue) of the CNS.

Currently, glia are broadly classified into 3 main groups:

– Astrocytes – regulate neuron functions, synapse remodeling, regulate Blood Brain Barrier (BBB), and more.

– Microglia – regulate immune response in CNS, facilitate efficient clearance of cell debris and by-products created as part of normal functions.

– Oligodendroglia – regulate production and turn-over of myelin.

Astrocytes are the predominant glial cell type, comprising approximately 40% of all cells in the CNS.

Astrocytes and Microglia are the glial cell types that are the main focus of our studies in the lab.

Note: we use the terms “glia” and “glial cells” interchangeably.

WHY ARE GLIA IMPORTANT?

The importance of glia in maintaining healthy CNS functions is underscored by the fact that:

(1) they are the primary responders to any perturbations in normal CNS functions;

(2) their own dysfunction is implicated in the root cause of numerous diseases (including many genetic diseases);

(3) volumes of neural tissue that lose their proper complement of glia for any reasons are no longer able to maintain viable neural circuits.

Bottom line: Healthy CNS tissue requires glial cells for viability and proper function. For CNS injuries, the lesions created at sites of tissue damage permanently lack glial cells (i.e. lost glia are not naturally replenished), and as such, there is no natural tissue regeneration at these lesion sites. In neurodegeneration, dysfunctional glia in combination with neural circuit loss contributes to disease. Maintaining neural tissue with healthy glial cell functions is fundamental to its continuing viability.

Glia interact directly with neurons to:

– Establish and maintain proper synaptic connectivity.

– Facilitate synaptic pruning and remodeling.

– Clear neurotransmitters from the extra cellular space.

– Provide metabolic support.

– PLUS many other functions.

Example immunohistochemistry image shows glia interacting with neurons in the mouse hippocampus.

Glia interact directly with non-neural cells to:

– Regulate the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) at CNS vessels.

– Regulate CNS parenchyma entry at the meninges.

Example immunohistochemistry image shows glia (astrocytes in green) interacting with endothelial and stromal cells at blood vessels and meningeal cells to form selective barriers that dictate access between neural and non-neural environments.

Adapted from O’Shea et al. 2020. Nature Communications.

Glia (ASTROCYTES) respond to CNS injury:

In traumatic CNS injury such as spinal cord injury (SCI) and stroke, the destruction of discrete volumes of neural tissue initiates a wound healing response coordinated by locally surviving glial cells.

We have characterized the wound repair functions of astrocytes in traumatic CNS injury in adult rodent model systems. Astrocytes undergo temporally dependent morphological, molecular, and functional reprogramming after injury that functions to constrain and isolate non-neural lesion cores and protect adjacent viable neural tissue. However, because this wound repair response is delayed and transient, it only results in a narrow, protective astrocyte border and not the comprehensive neural parenchymal repair that is needed for functional regeneration. By contrast, neonate mammals do show comprehensive parenchymal repair after CNS injuries due in part to the heightened states of self-renewal and migration in their immature astrocytes. However, neural parenchymal repair capacity is short-lived and is completely lost after the first postnatal week of development because astrocytes become quiescent and non-migratory cells as they mature. Strategies to manipulate natural astrocyte wound repair responses to enhance astrocyte proliferative and migratory capacity is being explored by our lab to improve recovery outcomes after adult CNS injuries.

The dynamic astrocyte wound response process is exemplified below for an ischemic stroke lesion, where astrocytes (green) respond to isolate a non-neural lesion core (red) from viable neurons (magenta) over a 42 day (d) time course.

Adapted from O’Shea et al. 2020. Nature Communications.

Glia (ASTROCYTES) respond to implanted deviceS:

Glial cells are also important contributors to the CNS foreign body response (FBR) to implanted neural devices. In particular, astrocyte border formation is a central feature of the CNS FBR and is derived from adaptive reprogramming of astrocytes (somewhat analogous to the astrocyte wound responses to CNS injuries described above). How, and how many, astrocytes are reprogrammed into border states ultimately determines the extent of neural tissue disrupted around devices. The severity of the tissue disruption and the induced FBR may be dictated by definable device properties, such as surface chemistry, topography, bulk geometry, and mechanical properties. Ultimately, the CNS FBR and the associated astrocyte borders that are formed cause problems for the long-term functions of neural devices that compromises device performance and can lead to premature device failure.

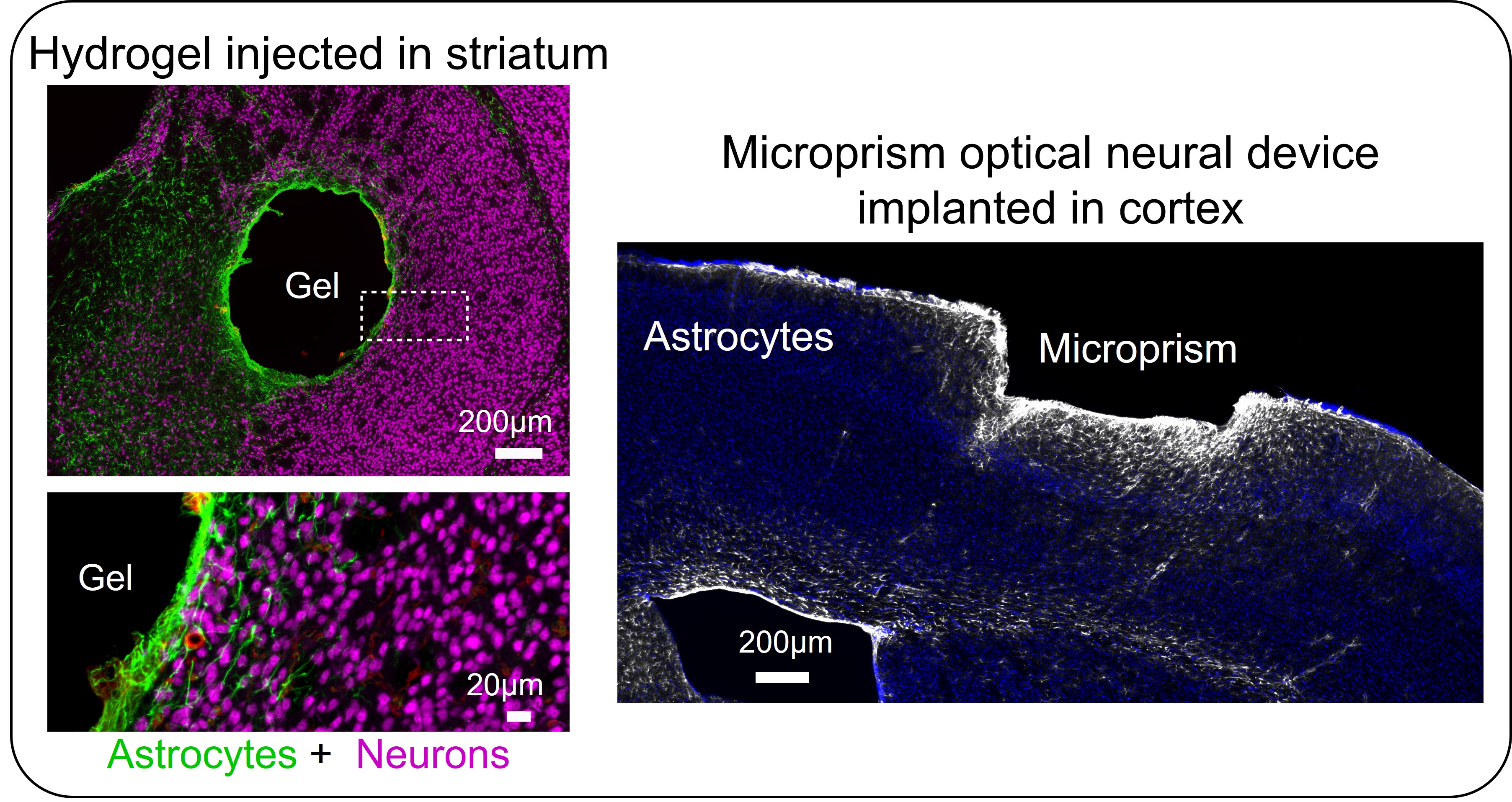

Astrocyte borders form around all manner of devices applied to the CNS including injected drug releasing hydrogels and implanted optical neural devices such as microprisms (see images below). Developing astrocyte border-regulating strategies will be required to improve the performance of neural devices and is a key focus area in our lab.

Adapted from O’Shea et al. 2020. Nature Communications.

DYSfunctional glia (MICROGLIA) may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases:

When glia become dysfunctional they can exacerbate the progression of neurodegenerative disorders by contributing to early-stage neural circuit damage that can precede clinical presentation of disease. For example, microglia, as CNS innate immune cells, readily clear misfolded or damaged proteins. Failure of microglia to clear neuron-released α-synuclein and amyloid beta (Aβ) via phagocytosis, altered lipid metabolism, or iron accumulation in microglia can exacerbate neurodegeneration. Modulating microglia lysosomal function, lipid metabolism, and phagocytic capacity may be viable strategies to attenuate disease progression. In our lab, we are exploring glial cell specific therapies that could be applied locally to correct glial cell dysfunctions that contribute to neurodegenerative disease.

OPPORTUNITY:

Despite playing prominent roles in heathy and disease contexts, developing therapies that regulate and manipulate glial cell functions has received little attention. We see a significant opportunity to use our unique expertise in glial biology and biomaterials engineering to develop new strategies to treat CNS disorders by directing glial cell functions.